Travis Louie Paints Local Characters, Sideshow Carnies & Loveable Monsters

“My animal-like characters are stand-ins for all of the different ethnicities who came to this country looking for a better life.”

Share Article

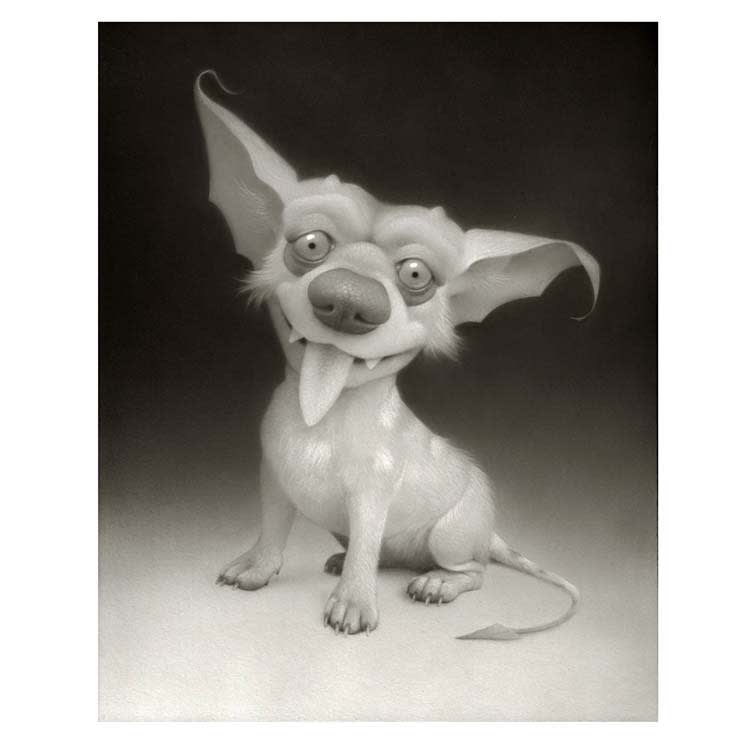

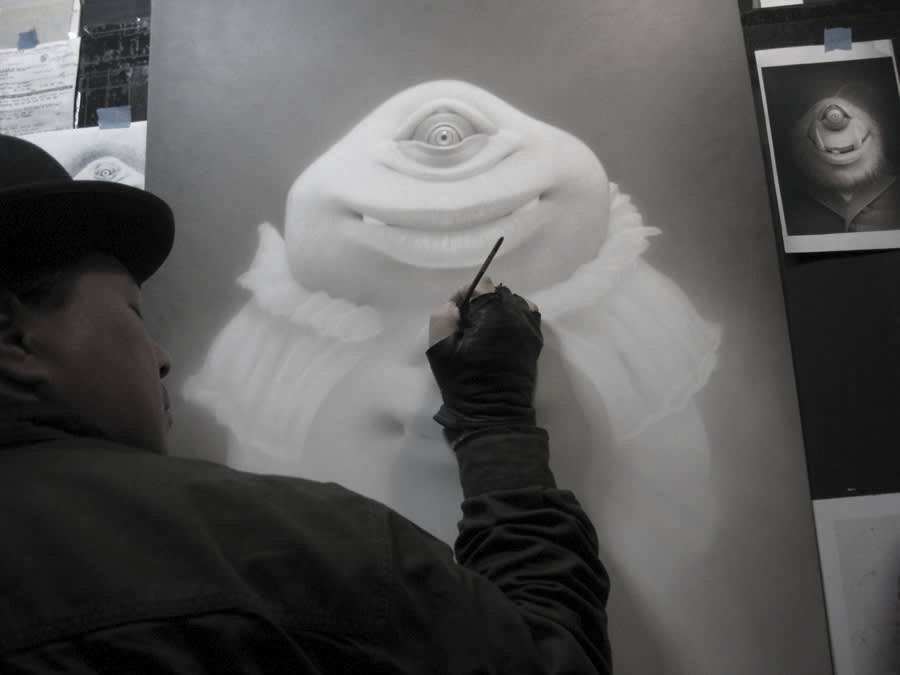

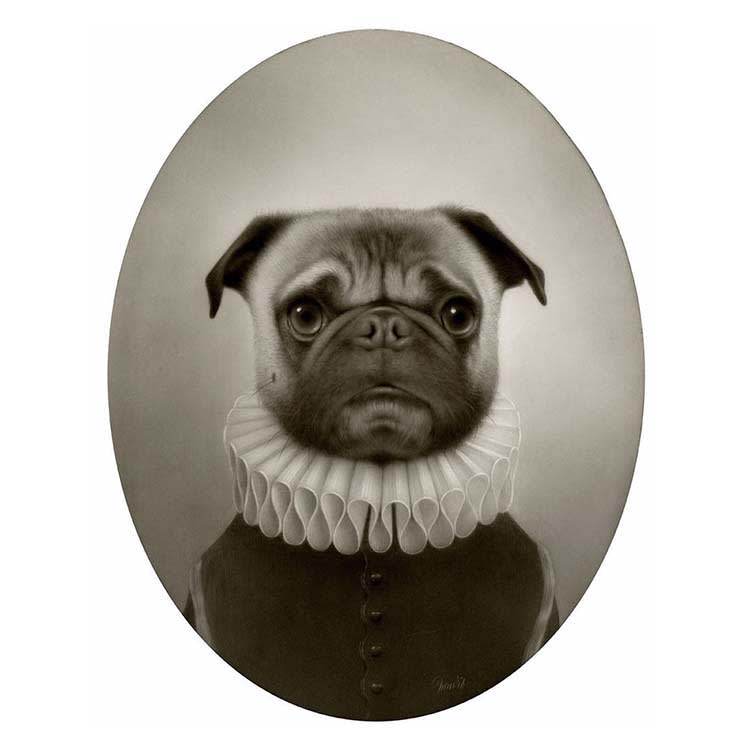

The deadpan understatement with which Travis Louieopens in new tab depicts his subjects belies their fantastic pedigrees. Louie’s black-and-white paintings, which draw from Victorian portrait photography and 19th-century documentation of traveling “carnies,” have been featured on covers for the New York Times and shown internationally, including a solo show at KP Projects in Los Angeles. Louie treats his hybrid creatures — lifted from another time or another world — with unfailing empathy, and his biomorphic protagonists bristle with whimsy and anima in equal measure. Louie’s irreverent creatures embody the assertion of Lewis Carroll’s Cheshire Cat that “imagination is the only weapon in the war with reality.” We chatted about finding inspiration in the immigrant experience, naturalist illustrations, and Coney Island.

Your human and animal subjects have distinct, striking countenances (similar to Victorian portraiture). How do you capture faces and expressions?

I consider myself to be a professional “people-watcher.” The expressions that I give my characters are based on those of people I’ve seen either in town [Redhook, New York] or when I am traveling. I like to take note of certain features that stand out. There used to be a local fellow with these great big mutton chops and a nose that rivaled Walter Matthau’s. I turned him into a positive “thumbs up” guy with horns.

The affinity between your works and the biological illustrations of artist-naturalists like Audubon is striking to me. Those 19th-century works strive for objectivity, while your animal subjects (even those based on species that exist in the world) have their own visceral internal lives. Can you speak to this tension?

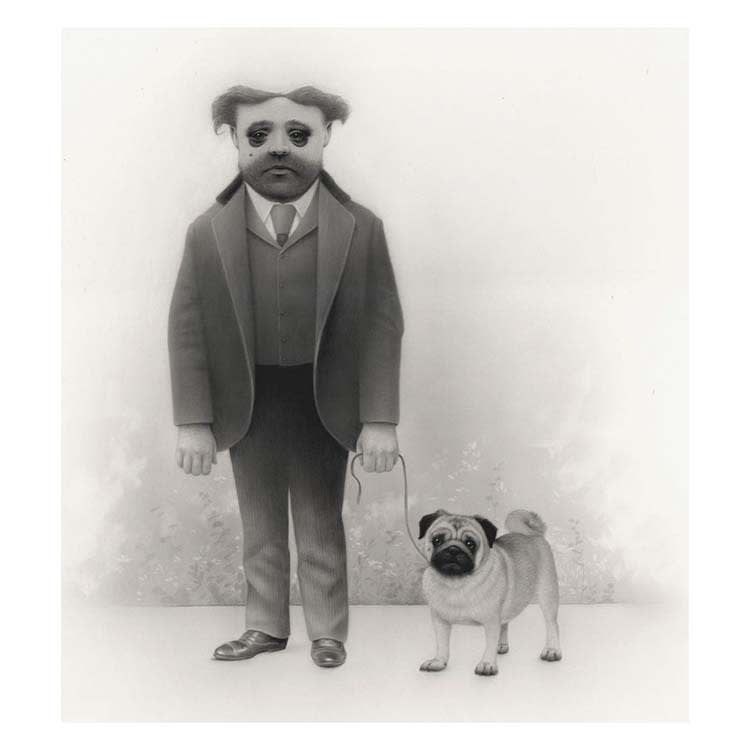

I’m influenced by my connection to the immigrant experience. My family came here from China, and my animal-like characters are stand-ins for all of the different ethnicities who came to this country looking for a better life. But the paintings are also inspired by the 19th-century photographs I collect. I have thousands of them in my files. I have more than a passing interest in the early naturalist illustrations by [Renaissance naturalist] Maria Sibylla Merian. Her carefully detailed paintings of insects are remarkable.

Similarly, you’ve mentioned your early interest in Coney Island sideshow performers — frequently portrayed by immigrants, who were themselves navigating a foreign world. What draws you to these people?

I’ve always been interested in sideshow attractions. I grew up going to Coney Island on weekends. I’ve always been fascinated by the rich history of those amusement parks like P. T. Barnum’s American Museum, which was located in Tribeca in the mid-19th century. I often write out backstories for my characters. I try to flesh out what kinds of jobs they may have had. Some of them were indeed performers in the little alternate universe I’ve created.

You've described your early exposure to the film Nosferatu and other fantastic movie characters that are depicted as other than human, or even monstrous, but the beings you paint are so likeable.

I certainly have a soft spot for monsters, going back to when I was a kid buying “Famous Monsters of Filmland” at the Five and Dime and watching age sci-fi films on local channels. I managed to see Nosferatu (1922) by chance because a public broadcast station was airing a weeklong celebration of influential foreign films, which also included Akira Kurosawa’s Rashômon (1950).

The six-year-old Travis was mesmerized and maybe a little scarred for life. My sympathy for the “monsters” in my paintings comes from my own fears of being misunderstood, which is connected to my experiences with racism as a small child… There is this sense of being “the other,” despite the generations of my family that have been in this country since the end of the 19th century.

Can you describe how stories operate in these paintings? What sparks them? How legible are they intended to be?

The stories are a starting point for many of the paintings. They help me breathe life into my characters. They are informed by many things I’ve experienced or have been exposed to. Sometimes it could be as simple as seeing a person eating a sandwich at the county fair or a person walking their dog. I can be inspired to make a series of thumbnail sketches on a placemat at the local diner. It is often very spontaneous.

I read that you and your wife collect frogs. How are they doing these days?

Yes, we have several species of amphibians in our house along with tarantulas and a small Pug dog. Every day we have a routine that is not dissimilar to that of an amateur zookeeper. But I love them all so much!

Cat Kron

Cat Kron is a writer and editor covering art and culture for publications including Artforum, Art Review, Cultured, and Contemporary Art Review LA. She has a novelty sweatshirt with an Edward Gorey illustration of a tuxedo cat lying on books and the caption “books. cats. life is good,” as well as her own tuxedo named Batty, whom she shares with her husband.

Related articles

![Painting of skeleton riding cat with heart below]()

Artist Gary Baseman on Late Cat Blackie & New Kitten Bosko

“Blackie was a friend and a collaborator. I never saw him as a pet and I don’t see Bosko as one either — they are family members.”

![painting of a women in the bath]()

Sofie Birkin’s Art Is Feminist, Fantastical, and Fiercely Queer

“I think the relationship between a woman and her animal companion can build out a character a lot — they’re more like witches’ familiars than pets.”

![Illustration of a woman sitting at a table with two cats]()

Artist Livia Fălcaru on Felines, Feelings, and Dream Fashion Collabs

“I just simply like the idea of cats and their specific things. Throwing in a cat is something that comes naturally now when I make an illustration.”