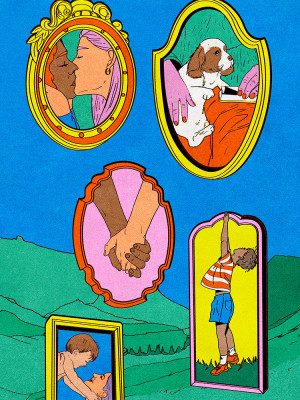

So, You and Your Partner Want to Live Together—But Your Pets Don’t

Your cat can’t hide from the dog in the attic forever. What do you do now?

Share Article

Heavy Petting is a weekly column full of relationship advice for pet parents—so you and your boo don’t end up fighting like cats and dogs over the cat and dog.

The search term I Google, more than any other, when I’m having a vulnerable, no-good, bad day is: “unlikely animal friends.” All I want to see is a puppy snuggling a piglet surrounded by a little crew of ducklings, all napping in a tin pail. The unbearable cuteness is what I’m seeking — but also the rarity. The “unlikely” quality of this friendship is what makes it a worthy documentary subject.

The truth and the reason these relationships are remarkable is that many animals Do. Not. Want. To. Be. Friends. In fact, many of them just want to snarl and growl at each other. And this antagonism — or the fear of it — can be an obstacle in relationships, especially when two people want to move in together and combine their little families.

The story of two unlikely roommates

Before he met me (his current best friend), Finn, the dog I now share with my partner, Megan, was best friends with a cat named Corsica, who was Megan’s former roommate’s cat. Both Corsica and Finn have gorgeous brindle coats and a flair for drama. They ran a short con in which Finn would bound up to the back door and cause chaos enough for Corsica to escape into the yard. We believe Corsica paid Finn by knocking food off the counter onto the floor.

Because of his hunting lineage, I would have assumed Finn would be the problem with an introduction of a new cat into the mix — he was not. Just before Megan and Finn moved out of their apartment, a third roommate moved in. He brought another cat (name not remembered by anyone at the moment). The blended family did not blend. There was total warfare between Corsica and this new cat, launching from the top of bookshelves, etc. Finn was caught in the middle, all the humans were distraught. The living situation was very tense as Finn said his final goodbyes.

When the compromise isn’t a perfect one

When some of my favorite friends to visit (they live in a rambling, beautiful Western Massachusetts home) moved in together, one of them brought a beloved, doofy dog; the other a beloved, but ultimately spiteful, cat into the mix. Since they’ve lived together, the cat permanently camps out in the attic, unless the dog’s in the yard. Meanwhile, the dog’s always attempting to court the cat for friendship, which just makes the cat more righteously grumpy.

“But don’t cats perversely enjoy being righteously grumpy?” my friend asked me. “It seems like one of their main personality traits.” But she knows that “it’s not a perfect situation. Compromises kinda suck.” In general, cats come across as very cool; they don’t really seem to respect any form of compromise and are generally above such things. Plus, they tend to create their own boundaries.

As certified cat behavior consultant Mikel Delgadoopens in new tab confirmed, my friend’s cat is simply doing what any cat would do when a dog comes into their home: taking space. “Cats need to feel safe in their environment, so a dog-free room or wing is important.”)

Kelly Scott, a couple’s therapistopens in new tab with Tribeca Therapyopens in new tab, says she’s seen couples work through very similar dynamics, especially when they’re bringing already existing pets together when they move in. She recommends a mediation approach: “Literally sitting down, and asking: ‘Where are you willing to compromise?’ Because if there’s resentment attached, we gotta go back to the drawing board. What’s toxic in a relationship is when sacrifice leads to resentment. It’s like poison.”

But Kelly doesn’t recommend pessimism about the situation before the couple thinks through all the options. “People can often be tempted to go to the worst outcome rather than think of a solution like hiring specialists trainers or changing the set-up of your home,” Kelly says. “It’s about really being disciplined and creative looking at every possible available option.”

The impossibility of a second pet

When my friend Anna moved in with her partner Jordan, he already had a dog — big, burly, beautiful Shenandoah. Anna loves Shenandoah, but Anna always wanted a dog who would go running with her, especially after they moved from Boston to Idaho. Meanwhile, Shenandoah’s personality is somewhat akin to a hibernating bear, who hates walks as much as he loves napping on the floor.

Shenandoah was a puppy during deep lockdown and never got to socialize with other dogs. So, Anna’s partner resists even looking at other dogs; it would be unfair to Shenandoah to learn to share space. For Anna, this feels “like just because Jordan got a dog first, it gives an overriding power about any future decisions.”

Of course, Shenandoah’s happiness is imperative, but Anna thought that with some work there was a possibility Shenandoah could get along with another dog. Jordan got the bonding experience of raising a dog since puppyhood; and Anna is jealous she won’t get the same experience — for years at least — because Jordan didn’t want to see if Shenandoah might be up for it.

After all, Anna and Jordan aren’t wrong: introducing animals can be tricky. Mitchell Stern, a dog trainer with Yes Dog Trainersopens in new tab, notes that even with the most well-executed, careful introductions, you may have to have some permanent systems in place to make things work. The kitchen door may always need to be shut while the cat is fed to keep the dog out. “Anything that can trigger a resource-guarding behavior is important to avoid until the relationship is established, and possibly forever,” Stern says.

Why some pet pairings just won’t work

And as for attempting your own version of “unlikely friends,” like a bunny and a Basset Hound or a cat and a gerbil, Stern adds: “I want to state for the record: UGH. These types of situations are potential landmines… Imagine for a moment how stressful it might be for the prey target. In my humble opinion: It’s selfish of the owner not to consider the target animal and to think of themselves as Dr. Doolittle, egotistically thinking everybody will get along. These are animals, and animals can be unpredictable.”

As Brett Bailey, a dog trainer with Who’s a Good Boy Industriesopens in new tab says, “If you have a dog that has high prey-drive, and you have a bunny, cat, or anything that resembles prey, you are likely not gonna be successful at having the pets live together. Predation is a genetic anchor, and it will never go away.”

Meghan Rydzewski, a therapist at the Council for Relationshipsopens in new tab, has worked with a handful of couples dealing with this exact situation. Some have made the hard choice to remove one of their pets. Others have divided their home, peacefully, like a couple who had two dogs with a high prey drive and three bunnies. “Both partners agree that the bunnies’ safety is a top priority,” Rydzewsk says. “The bunnies have their own room in the house and are kept safe away from the dogs.”

Even though I periodically think about adopting a cat now, I put a pause on this instinct, because of Finn’s previous exposure to cat-cat warfare. But now, while I’m not entirely optimistic about Finn’s ability to get along with any cat — the opposite actually — but I do think of his beautiful unlikely friendship with Corsica, and I imagine that with the help of a skilled trainer and a lot of careful introduction, there could be another unlikely best friend for him.

Maggie Lange

Maggie Lange is a writer, editor, and columnist. Her work has been featured in New York Magazine, Vice, Guernica, GQ, Rolling Stone, Pitchfork, Elle, and Bon Appetit. She lives in Philadelphia with her favorite brindle boy, Finn.

Related articles

![an illustration of a cat with various cat chores: being groomed, scooping the litter box, feeding the cat]()

What to Do When Your Partner Isn’t Pulling Their Weight With Your Pet

So you don’t have to be annoyed anymore.

![a white dog stares up at a pink dress and yellow dress waving outside in the wind on a clothing line]()

When Is It Too Early to Get a Dog Together?

You’re in love, but is it irresponsible to add four paws to the mix? Here’s some input for your consideration.

![An illustration of 2 dogs on a bed]()

Three’s a Crowd: When One Partner Doesn’t Want the Dog in the Bed

You want them to cuddle up, your S.O. doesn’t. Here’s how to handle the great bed debate.

![Couple lies on the grass with their Malamut dog in the park]()

How to Woo Your Way Into Your New Partner’s Pet’s Heart

Meeting your new partner’s pet is an honor — winning them over is another story. Here are some tips for being friends with your significant other's best animal pal.

What It Takes to Convince Your Partner to Adopt a Pet

Can you spell “compromise?”

![A woman with black hair and green sunglasses hugs her brown Doodle dog]()

Should You Put Your Pet in Your Dating Profile?

Yesterday was “Dating Sunday” on the apps. Apparently, your pet pic is a great way to find a match.